Casper Friedrich Artes

A Biography

By Gloria M. Barron, great grand-daughter of Casper Artes.

This is the story of Casper Friedrich Artes, born in Merken, Saxe Meiningen, Germany, March 29, 1816. His mother died while Casper was an infant, and his father was burgomeister of Merken. Casper's father left the upbringing of his son in the hands of the boy's grandmother.

There had been many musicians, artists and poets in the Artes family, among them, Grandmother Artes' own husband, so the pious old lady knew from bitter experience that "artists" generally were paupers, unable to provide for themselves or their families. The strong-willed grandmother decided then, that any tendencies toward art which might be displayed by young Casper should be discouraged. She determined that he should study for a career in the Lutheran Ministry.

The child's inborn talent could not be suppressed. From the time he could reach the piano keyboard standing on tip-toes, Casper could not be kept from the instrument. He memorized every melody he heard, and then came home to re-create the tunes on the piano. "Oma", Casper's affectionate name for his grandmother, became concerned when neighbors commented on the childs unusual proclivity for music. When the boy's father commented one evening that the lad appeared to be a true prodigy, that was too much for the old lady. In order to frustrate Casper's artistic inclinations, Oma had the piano removed to the attic, thus removing the temptation. Never again was the sound of music heard in the Artes home, so long as Oma lived.

The old lady could not turn off the music that surged from within the boy's soul. At every opportunity, he would slip away and climb to the dusty attic, where he would fondle the keys and run his fingers silently over the smooth black and white ivory. Soon Casper found that by detaching the strings inside he could "play" the piano without any sounds to give him away . . . only he could "hear" the music.

When time came for little Casper's first day at school, he exhibited the usual child's reticence, and Oma had to all but drag the protesting boy down the cobblestone streets to the school. As they neared the school the magical sounds of a piano, floating from the music room, caught the child's ear, and his protests stopped. This did not escape Oma's attention, and she became apprehensive, but the boy must be educated. She hoped that with her guidance the boy might be directed into other channels.

Casper did well in his studies. He spent every free moment - recess, lunch time and after school hours, standing hidden outside the door of the music room, listening and watching as the other children received the lessons which were forbidden to him. Casper memorized every sound, every position of the fingers, then, when the class was over and the room empty, he would slip inside to practice what he had learned.

He practiced this "self-instruction" for months without detection, until one day the young music instructor returned and heard Casper playing. The instructor stood silently behind the little pianist and listened as the boy ran through the intricate exercises with exacting perfection.

Turning to leave, Casper's face blanched with fear when he saw the instructor. "Who taught you to play the piano like that, Casper?" asked the instructor. "No, no one, Herr Meister." "No one?! Come now, that was a very difficult, advanced exercise you were playing. Where did you learn it?" Reluctantly the boy told the instructor how he had watched from outside and practiced later when everyone was gone. The instructor was impressed by the young lad's ardor, and suggested that Casper enroll for instruction. Casper sadly explained that this would be impossible, due to his grandmother's stern injunction against music. Loath to allow the boy's talent to go undeveloped, the instructor told Casper he would teach him in secret. And thus, Casper's musical tutelage was begun.

The young music instructor also worked as the church organist, thus he had access to the mighty organ, and was able to introduce Casper to the instrument on which the boy was destined to become one of the world's foremost artists.

The instructor had persuaded the parish priest to ask Casper's father if the boy could work in the church on weekends, running errands, helping to do what needed to be done. Oma, unsuspecting, was delighted to have the boy work in such an environment, so Casper was able to practice every Saturday and Sunday on the great organ, without his grandmother knowing about it. During the summer vacation months, Casper had even more opportunities to practice, and his genius flourished.

The music instructor became convinced that the boy could become a great master organist - but he would need more advanced instruction and constant practice, which was impossible under the restrictions forced upon him. Soon, the instructor knew, Casper's grandmother would have to be told of the boy's talent and his potential destiny.

Oma's enlightenment came in dramatic fashion that winter.

Casper's father came rushing home one winter evening, breathless with the exciting news that King William Friedrich III was touring the country, making personel appearances ... and that the king would be in Merken on Christmas Eve! As Burgomeister, Casper's father would have the pleasurable duty of greeting the royal party! The whole family would sit in the pew right behind the king, during midnight mass.

On the day of the king's arrival, work crews were out at dawn, sweeping the snow from the streets and walks. Banners and bunting were hung everywhere. In the church, Casper polished all of the candlesticks and placed new candles in them, as the priest unwrapped the new alter cloths and vestments which had been saved for just such a special occasion. The king was very pleased with his reception.

As everyone filed into the church for mass, though, a "crisis" developed. The young organist stopped the Burgomeister outside the church and told him that his page turner had taken ill -- could Casper fill in for him? His father agreed to let Casper help the organist.

From the very first chord heard, as the sound of the great organ filled the church, everyone was aware that there was something awesomely different in the sound. There were comments buzzed about the church, to the effect that the young organist was certainly out-doing himself, no doubt inspired by the presence of the king.

The organist, of course, was young Casper. Hesitant and frightened when the instructor first pressed him into service, the boy lost all of his fears as soon as the first mighty notes rose from his touch. He was totally immersed in the music as he played.

King William was visibly impressed, and after the services, he asked that the magnificent organist be brought before him. When the instructor brought Casper down from the loft, the king could not believe it. "I ask to see the organist, and you bring me this child!" protests the king.

Despite the assurances of Casper's tutor, neither the king nor anyone else could believe it was actually the young boy who had brought forth such masterful sounds from the organ. The king insisted on being taken to the organ loft, where he commanded Casper to sit at the organ. "You will play for me again, and this time I shall watch!"

The boy played and there was no question in anyone's mind that he was, indeed, the master organist they had heard. The king grew misty-eyed as he listened to the boy's playing. As the last note died away there was a long moment of silence. Then the king spoke, emotionally. "You are indeed Little Mozart, come back to play for us again!" Royal endorsement was bestowed upon Casper, and he was given permission to use the title "Court Organist".

After this event Grandmother Artes could no longer refuse permission for Casper to enroll in advanced studies. However, she stipulated that he was to continue his regular schooling, as well. If he could not live without his organ music, well and good -- but his career was still to be that of the ministry. Casper would accepted these conditions, ANYTHING, just so he could continue his music!

Casper's fame as "Little Mozart" spread far and wide, and he was called upon to play the organ at church feasts and in concert all over Germany, but his genius was not restricted to music. He was a truly phenomenal scholar, and at the age of fifteen he was accepted at the University of Heidelberg, where his preparations for the ministry began in earnest.

Casper ranked high in all of his classes. He became a master in languages, fluent in English, French, Hebrew, Spanish, Arabic, Italian and Latin. He was a particularly avid scholar in philosophy. He was a well rounded student, taking part in all activities. He even acquired the traditional student's badge of honor -- the accolade scar of the dueling sword.

His true love, however, remained music. He discoursed passionately on the subject any time he could get his grandmother to listen. It wasn't until Casper was seventeen and visiting at his grandmother's death bed, that the old lady finally relented. She had done all she could to give him a useful, purposeful life, but he was obviously by nature an artist. On her death bed, Oma released Casper from his promise to become a minister, and freed him to make music his life.

Casper was twenty-five when he met and married Anna Catherine Bierschenck in 1841. In the years that followed Casper learned what his grandmother meant when she spoke of the hardships in the life of an artist. Faced with a constantly increasing family, Casper could no longer subsist on the stipend that the royal patronage as court organist brought him. To supplement his income, Casper gave organ lessons to the young people of Leipzig, and even took a part-time job teaching in the Hebrew school. Less and less time was available for his own music studies. Casper and Anna had a total of thirteen children, six of whom were born prior to 1851, thus his family required more and more of his time and energy to support them.

During the late 1840's a great wave of militarism was sweeping across Germany - a wave that was to reach its crest in the Revolution of 1848-49. Many musicians, like Richard Wagner found great inspiration in the militancy of the times, and expressed it in their music. Casper Artes, however, saw that the unrest threatened the liberty of the German people. He became an outspoken opponent of the militaristic power of the Kaiser and a champion of civil liberty. Thus Casper's name was enscribed as a "socialistic agitator" who must be dealt with. Fearing for the safety of his family, Casper decided he must leave his homeland to seek refuge in America.

He and Anna made their escape plans in secret, and through the help of influential friends, they obtained passage to America on a sailing vessel. In order not to arouse suspicion, they could not be seen preparing to leave, and when they did depart it was by dead of night - leaving all of their cherished possessions behind, taking only the clothing needed for the trip. All of Casper s beautiful music, operas left behind, later to be destroyed in vindictive revenge.

After six stormy weeks at sea, Casper and his family arrived in New York City. The year was 1851. With his family safe in an apartment, Casper entered on a round of interviews with various employment prospects. One day while looking for work he happened to pass by the Old Trinity Church ... and what happened was described in a newspaper article, as follows:

"...hearing the organist of Old Trinity at practice, Artes ventured in, introduced himself, and was invited to try the organ. He sat down at it, lost himself in the swell of its splendid volume and purity of tone and played away in a mood of ecstasy, while the church organist sat in amazed delight, himself lost to all but the wonder of what he was hearing, ... the sightseers in the churchyard and passersby on Broadway were drawn into the church by the majesty of his touch, until, when he had ceased playing in a low and plaintive diminuendo, it was to discover the church crowded almost to overflow capacity. The people stood in awed silence. The church organist was overcome with tears. It was as if some Pied Piper of Hamelin had newly risen and come that way to charm the grown children of the metropolis!"

After this story appeared, other reporters came to Artes, inquiring about his background for "followup" stories about the "Pied Piper" who had caught the public's fancy. With this publicity to recommend him, job offers flooded in to Casper and it became a question of merely choosing where he wanted to practice his art.

Anna found New York City terrifying, The only time she ventured out of the apartment was to buy fresh food from the pushcart vendors that passed each day. One day Anna purchased a basket of large delicious-looking plums as a treat for the children. After a couple of bites, the children indicated something was wrong with the plums, so Anna tried one herself. There WAS something wrong! She rushed to a neighbor's apartment and asked what this strange fruit was. Told it was a tomato, Anna blanched and rushed back to her children. Tomatoes, as everyone knew, were deadly poisonous! Anna quickly tossed out the remaining tomatoes, so Casper couldn't accidentally eat one, then she gathered her children about her in a circle. Fully convinced they were all going to die, Anna forced herself to be calm, and sat telling the children stories, while waiting and watching for the convulsive death-throes she was sure would appear soon.

When Casper came home that day, he convinced Anna that the tomatoes were perfectly safe, and calmed her fears, but New York City remained a fearsome nightmare to Anna. Casper lovingly reassured his wife that they would find another place to live ... a place where fields were green, where she could have her own garden again, and bring up her children in a familiar comfortable environment.

Casper accepted an offer from a group of men who were founding a seminary of arts in western Kentucky. Casper packed up his family and they set out on the long and harrowing trip to the sleepy town of Henderson, Kentucky. They travelled part of the way by steam train and the remainder by steamboat, down the Ohio River.

The seminary blossomed and prospered from the very beginning. All indications pointed to a great financial as well as artistic success. Then, at the end of the first year, the founders of the seminary suddenly disappeared, absconding with all funds and leaving the staff unpaid and stranded. The teachers attempted to keep the seminary operating and pay off the debts left by the founders, but one by one, the staff dwindled until only Casper Artes was left. It was his duty to close the seminary permanently.

Another great personal tragedy occurred during this period when Casper's and Anna's six-year-old Theresa contracted diphtheria. The two sat up day and night with their daughter, praying for a miracle. en the doctor made his house call on the third day of Theresa's illness, he had to give the tragic news that the child had but hours to live, nothing could save her. Interviewed years later, the doctor recalled the story in these words:

" ... When I called the third day and recognized that my good brother, Death, had signaled his coming in an hour or two, I could not leave them in their loneliness, and dared not hide the truth. I told them as gently as I could, sitting there by the little bed. 'She will be beyond all pain in an hour,' I said to them. And I can see the professor yet, with a set face, rise and walk firmly to the next room, seat himself at the piano and begin to caress the keys with infinite lightness into old airs some of the familiar to me. Somehow it shocked me that he could play the piano at such a moment. I fancied he had not understood me and so I resolutely rose, went in to him, and putting my hand on his shoulder, said, 'Did you understand me? She is dying!' 'Yes!' he nodded. 'I know. But these are the songs that sung her into life and to sleep many a night from back in the old country until now. I play them to her once more for her last sleep. Maybe she will hear, maybe she will know.' And there for an hour we sat in the two rooms until the music, and the little life, died softly, together."

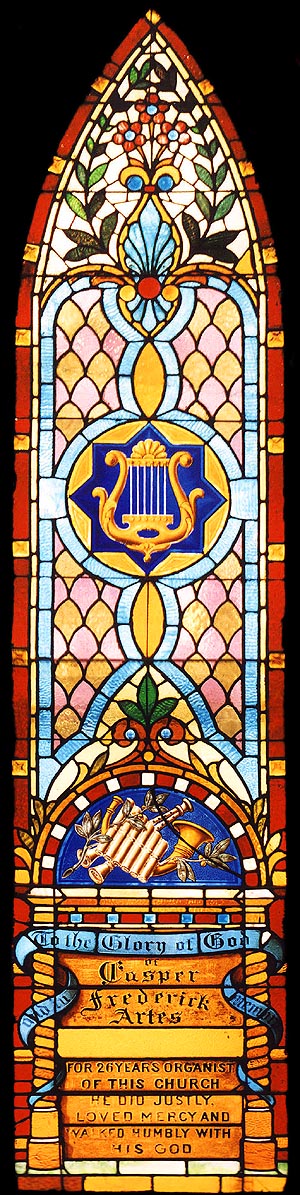

Casper accepted a position with St. Paul's Episcopal Church in Henderson, and supplemented his income by giving private instructions in music and academic tutoring to the young people who needed more advanced schooling than the public schools could offer. He was to remain St. Paul's organist for more than a generation. Church records show that he did not miss a single service in thirty years.

When the Civil War broke out in America, life became hard for everyone, but particularly for Casper and Anna, whose family had increased steadily. Music lessons became a luxury no one could afford, but Casper continued to instruct the truly promising young musicians at no charge. Quite often he was paid in much needed foodstuffs.

Casper and Anna saw five of their children die in infancy. Perhaps the five little graves in St. Paul's cemetery are part of the reason Casper remained in Henderson the rest of his life.

He was known as "The Professor" or "The Old Music Master." The affectionate esteem in which he was held is difficult to define in terms of present day values and ideals, but there was a wondrous love affair between Casper Artes and the little town of Henderson which equals the love affair between, say, Lincoln and the Union - or Lee and Virginia.

After so illustrious a beginning, and so exciting and dramatic a life, it seems incongruous and anti-climactic that Casper's life story shold end in such quiet dignity.

One Sunday, as church goers filed out after services at St. Paul's, the old master organist finished playing his final hymn, closed the cover of his organ, ran his fingers lovingly over the smooth wood, then leaned forward and rested his head on the instrument. No regrets. No dreams of "what may have been." Casper Artes had completed his journey, and it was a successful one.